The Right Size - Questions of Growth & Scale for Fiscal Sponsors and Projects

The subject of strategic growth and scale has become a central question for the fiscal sponsorship community. The forces of growing social, racial, and economic inequity in our country, compounded by the pandemic, have fueled both a rush of beleaguered organizations seeking refuge and safety in numbers, as well as accelerated growth in grassroots, social justice organizations seeking fiscal sponsors to accelerate their missions. Most fiscal sponsors are reporting tremendous growth in the demand for their support, and many individual projects are experiencing rapid and significant influxes of support and parallel increases in demand for their services. Questions about how to think about scale, whether to scale, and how big is big enough are top of mind.

The distinctly American obsession with bigger-is-better and growth-for-growth's-sake is deeply ingrained in our cultural values and has profoundly distorted our assumptions about the nonprofit sector, largely in unhealthy ways. The assumed value of bigness permeates manifestations, from the “Big Mac” to the spurious free-market mantra, “if you’re not growing, you’re dying.” Growth, accumulation, and scale are so deeply ingrained in American, capitalist culture that to deny their alleged “truth” is akin to asserting the earth is flat.

Today, more than ever, we must challenge bigger-is-better as our reigning paradigm and think about the value of scale and impact in a more multifaceted way, celebrating the value of both big and small and all things in between. For the private sector, growth and scale are mostly driven by market dynamics: the need for dominant (or some specific) market share, competitive advantage, and ultimately, profit. And with profit as the primary motive, scale, success, and value are naturally measured in money.

In contrast, the nonprofit sector, true to its name, is not motivated by profit (or money), but the fulfillment of charitable purpose, or mission. Yet, the growth-for-growth's-sake paradigm and the tendency to assess scale and value using the myopic measure of money prevails--a morbid condition induced upon the nonprofit community through private sector operating assumptions and values. When nonprofit leaders describe their organizations, the first thing out of their mouths is often a statement about the size of their budget. And I’ve found that most fiscal sponsors, when asked the same question, respond with the number of projects “under management” and cash throughput. But is that really why we’re doing this? And do those stats say anything substantive ultimately about impact or mission fulfillment? Not really.

For single-mission nonprofits, the question of scale is often tied to capacity building. Despite the fact that most of our sector is “small” in budget scale, the march to “professionalize” the sector over the past fifty years has forced nonprofits to scale for the sake of attaining a size that can support independent back-office and other infrastructure. (“If we were only bigger/had more money, we could afford a fundraiser, full-time accountant, etc.”) This brand of capacity building continues to be pushed by funders and the management consulting industry, often leading organizations to carry or strive for scale they cannot sustain, all in the name of being big enough to keep standing on their own. Of course, fiscal sponsors offer a solution to this problem: organizations can achieve a right size relative to their mission--even if that means at a modest budget size--while accessing full-charge, but fractional back-office supports.

If we are to move away from growth-for-growth’s-sake and growth-for-capacity’s-sake, whether we represent a fiscal sponsor or a project, we must ask the question, what is the right size for my mission? For fiscal sponsors and the nonprofit projects they support, the answer is complex. In our view, there are four considerable dimensions that inform strategic thinking about scale and impact for fiscal sponsors and their projects.

A Right Sizing Rubric

Our proposed Right Sizing Rubric may be used to think about scale for any nonprofit mission. But we share it here as a tool for analysis and consideration of scale for fiscal sponsors and their projects. The below rubric dimensions are relational: Impact & Mission Model relate directly to Culture & Working Relationships, and Financial Model & Capitalization relate directly to Human Capacity & Systems. Each of the dimensions represent areas of strategic decision making, and all four interact and affect each other.

A decision about Impact Model will affect matters of working and values-based Culture. For example, if your management culture has historically been “high touch”, rapid growth may spread your staff resources too thin too quickly and undermine the existing quality of relationships. A change in Financial Model will affect Human Capacity and Systems, and around the thinking goes. To state the obvious: if you grow in number of projects and income under management, your staff and systems will need to expand accordingly. Which of the below dimensions is driving strategic decision making may change over the course of time and organizational development, and at any given time, all four are likely to bear different weighting in strategic decision making. Despite the multi-directional way the decision process may flow, there is a general sense of flow of decision making that starts with Impact & Mission Drivers and follows the order in which the following descriptions unfold.

Impact & Mission Drivers

These are virtually synonymous in their use here and refer to what is motivating your work. Where does the impetus come from? Despite the tremendous diversity of missions out there, all missions are driven by a mix of two elements, or motivation archetypes: external motivations and internal motivations. Each of these offer different scaling considerations, each show up in different proportions and ways in nonprofit missions.

External Motivations are those that emanate from an external (to the individual or group of people that make up your organization), often quantifiable need, such as a population of youth to be educated, homeless housed, or a disease that needs to be eradicated. Scale and size of the nonprofit relative to mission is informed by the size of operation needed to address the external need, as delimited or proscribed by the organization.

Theories of change or impact focus on addressing the quantifiable need, usually within a certain demography, geography, and/or time frame. We might be decreasing numbers, i.e., people in Chester who are homeless; or increasing numbers, i.e., all children living in Santa Clara County have access to education and healthcare. External motivations are often the dominant drivers of health and human services, education, environmental conservation, and general community benefit, for example.

Internal Motivations are those that entail a set of decisions driven by individual or collective values, self-image, desired work-life balance, skill sets, and other considerations idiosyncratic to the specific person or persons that constitute your staff and board. In short, it’s the answer to the question, “What is enough?”. We make decisions about what is enough all the time: this is the right size house for me, or this is all I’m willing to spend on that new jacket. Organizations merely collections of humans making similar decisions. In the field of applied psychology includes the study of human satisficing (yes, that spelling is correct), the science behind how we decide what is enough.

Theories of change that are dominated by internal motivations often cleave to the individual or group sense of sufficient size, as determined by organizational leadership, or the whole organization team, if more collective work culture is in place. For example, if the potential of human creative imagination to think up new theatrical works is theoretically infinite, why does one theatre company have a bigger budget and put on more productions than another operating at a comparable level of artistic quality and in the same marketplace? If you were to read both of their mission statements, I would venture they both can argue they are fulfilling their missions to make theatre, just at different operating scales. Of course, a number of other issues contribute to answering that question: the genre (and audience interest in that genre), leadership’s skills in raising funds, marketing prowess, etc. But a big factor, in my experience, is simply the decision of the artistic direction concerning the size, volume, and expense of the work they feel comfortable producing.

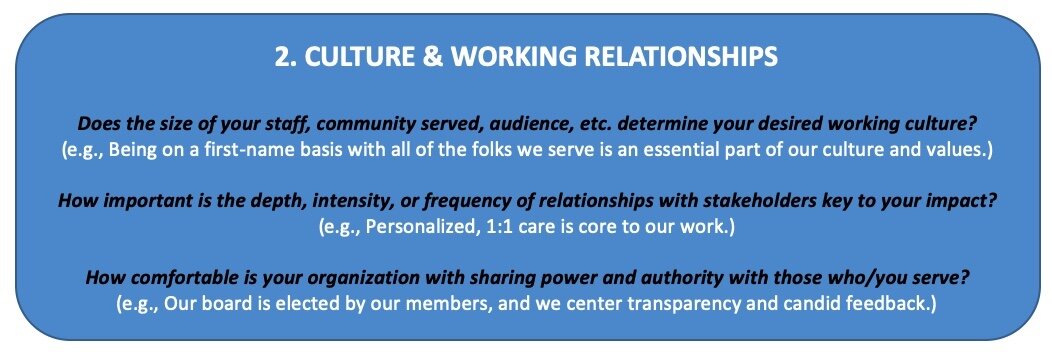

Culture & Working Relationships

Trust & Power Dynamics change with scale: as the size of your organization and/or number of audiences/beneficiaries increases, the ways in which you maintain trust in your work and distribute or share authority (if that is a value) changes. It’s not that trust is impossible or power cannot be shared in large-scale operations, just the way you structure and accomplish it needs to change, and thus factors into growth decisions and change management.

For example, it is often simpler (and may require less structure and process) to maintain trust and transparent relationships within a small group than in larger scale organizational systems, where it may be impossible or impractical for everyone involved to build mutual relationships. Rapid growth in staff teams can lead to instability, erosion of communication and trust, and other negative events, if intentional new systems and processes are not built to accommodate the changing dynamics.

Similarly, sharing power and authority, as in more “horizontal” or collective/cooperative organizational structures, may be easier to accomplish informally at smaller scale, but requires much more formal structure, process, and communications to do effectively at larger scale. This may be one of the reasons that more top-down, consolidated power structures are assumed to produce great efficiency at scale--the conventional “corporate” structure--and often emerge as organizations get bigger. More contemporary sociology of the organization has evidenced this does not have to be true. Holocratic organizational structures are on the rise and break larger organizations into semi-autonomous smaller units. Because it is usually true that making decisions within large groups of people is usually slower and takes more effort (coordination and process) than small-group decision making.

Social Ties & Relationships are considerations closely allied with the adobe trust and power, but speak more to the everyday work experience with and among your colleagues. Do you feel better working in a small group or intimate setting or in a large organization? The answer to this question drives job decisions everyday and it tends to become a shared value for some organizations. For many organizations, the ability to be on a first name basis with their beneficiaries is a desired or essential aspect of their impact. So, how to maintain that at scale can become a major cost driver. “Higher-touch” service models become very expensive from a staffing standpoint as the number of constituents they serve increases.

We cannot discount the importance of good old-fashioned chemistry: person-to-person working relationships. Even with the right skills, knowledge, intention, and experience, as with all kinds of relationships, some people just don’t work well together. In my experience, this basic, deeply human, and scientifically unexplainable factor has driven many decisions for projects to spin out, just as it often may drive the decision to quit a job.

Finally, when it comes to the scale of both your internal team and community of projects, there are a number of sociological and anthropological areas of study that look at the limits of human tie-building. Most notable of these is the theory of Dunbar’s Number, developed by British anthropologist Robin Dunbar. The theory basically maintains that there is a cognitive limit of about 150 people with whom any single person can have a sustained and meaningful relationship. It’s interesting that many coworking or collective organizations naturally plateau at around that size. Likewise, corporate and team dynamics change greatly at 50 people and then again around 150. I have found it notable that most fiscal sponsors top out at between 75 and 150 projects. Could that be Dunbar’s Number at work?

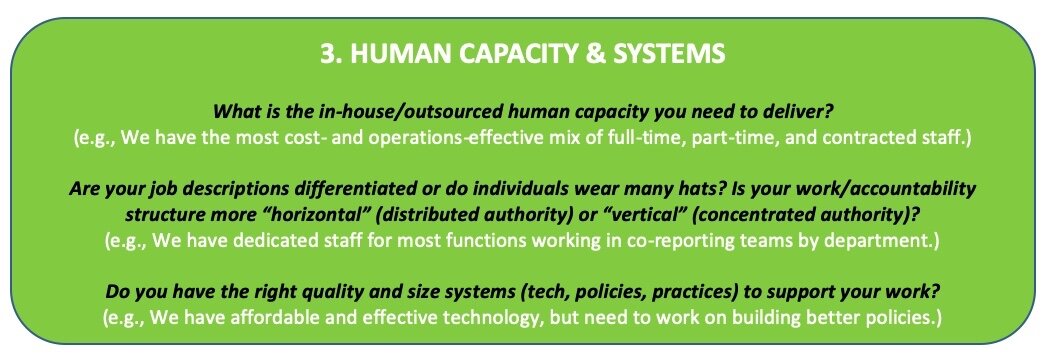

Human Capacity & Systems

Staff & Contracted Services are the chief driver of cost (and revenue) considerations when contemplating both scaling up and scaling down. Since fiscal sponsors are really in the business of shared services, this means shared people power, making staff and contracted services the largest fixed cost we carry, above occupancy and other major cost centers. (This is in fact true for most nonprofits.) So, the manner in which you are meeting service demand through a balance of in-house and outsourced human capacity is the key to sustainability and effectively managing growth.

Taking on large projects (or spinning them out), in particular in “Model A” settings, can have a profound impact on staff, and thoughtful up-staffing doesn’t happen overnight. We need to build more fiscal sponsorship-focused temporary services to allow sponsors to expand and contract with greater ease and less risk. Many of the relationship and capacity building functions fiscal sponsors hold are hard to temporarily source, owing to the need for specialized knowledge of the fiscal sponsorship environment. But some functions, such as bookkeeping and financial management, lend themselves easier to outsourcing.

Systems, like staff and services, need to be both robust and scalable (up and down). Here we mean things like workspace, enterprise technology, practices, and policies. These elements of the management system, in particular technology, often are overlooked or underestimated in their limitations to accommodate expansion and contraction. Chief among these--and the reason Social Impact Commons started our enterprise technology resource development with Sage Intacct--are the accounting systems that are essential to all fiscal sponsorship practices. There is no fiscal sponsorship without superior financial management systems.

Owing to the substantial cost and labor of implementing enterprise technology systems, fiscal sponsors often wait until a major expansion is afoot to think about upgrading in the interest of future scalability. In this case it’s easy to get caught behind the eight ball, and rushing to catch up can be a messy and expensive process. While, in concept, re-examining policies, processes, and practices should be less expensive, they too often are overlooked in moments of growth. Don’t underestimate how growth may bring about the need for new or more robust policies and processes.

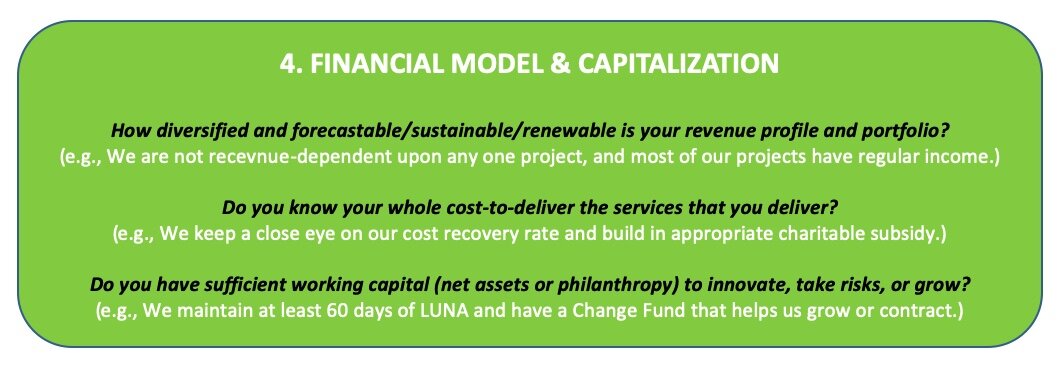

Financial Model & Capitalization

Operating Revenue Model and overall “portfolio management” is essential to any right sizing conversation. We’re discussing it last not because it is of less importance, but because the approach to resource or revenue model often requires decisions concerning the above dimensions of our rubric to be made first. Once you have set the scope and boundaries of your right size (for a given period of time), and determined what people power and systems you need to operate well, then it’s a question of achieving a sustainable revenue model with reasonable risk accommodations. That said, you may be operating in a philanthropic environment or at a scale where other constraints exist on your revenue streams (such as lack of available unrestricted operating support, which is all-too-common for fiscal sponsors).

For fiscal sponsors, there are some specific scaling considerations relative to sustaining core operating staff and systems: larger overall financial project portfolio and “throughput” can enable more shared infrastructure costs to be covered through cost allocations (fiscal sponsorship fees). In other words--assuming careful portfolio management--the more funds you steward, the closer you may get to 100% cost recovery and the less reliant you may need to be on direct philanthropic subsidy.

Many (possibly most) fiscal sponsors support large numbers of start-up and grassroots organizations, which definitely is an enduring area of growth on the nonprofit landscape. Whilte core to the mission of many sponsors, organizations of this nature tend to be volunteer driven (initially or permanently) and limited in their ability to forecast income, if there is any substantial income to be generated at all. At the same time, start-ups require a great investment of effort from sponsor staff, in balance making them high-cost and low-income, from a sponsor’s perspective. Start-ups and grassroots organizations require more direct philanthropic subsidy, or a portfolio model that relies on larger more established projects for most of its cost recovery. Whether by intention or accident, fiscal sponsors often engage in a kind of internal cross-subsidy: large project fees subsidize the cost to support smaller-budget projects. Consistent portfolio review and understanding the “elasticity” of the portfolio relative to income and support expenses is important.

Capitalization is key to managing right sizing, both up and down, in particular when it comes to the investments needed in people and systems. The bind for sponsors always comes in the need to invest in systems and people in advance of taking on a large or complex new project (or projects), knowing that cost recovery once the project is on board will take time. This is where working capital comes in. But like most of the nonprofit sector, we know anecdotally that many sponsors operate with only thirty days of unrestricted funds on hand. And most of those funds are needed for existing cash flow management, not investment in impending growth.

Building and maintaining a healthy balance of Liquid Unrestricted Net Assets (LUNA), if possible 90 days or more, is one approach. This can only happen with consistent budgeting (at the project and fiscal sponsor levels) and attention applied to stocking cash reserves. While not a standard practice, more fiscal sponsors may want to consider a fractional increase in their allocation rates to contribute to cash reserves. Restricted fundraising for a board-designated Capital Fund is another approach. Both are hard for many fiscal sponsors. Despite a decade of growing awareness in the funding community over the lack of capitalization in the sector, there are still very few grants available for capital reserves development. This highlights the potential need for shared revolving capital, privately assembled and/or through commercial lines of credit, for the fiscal sponsorship community in general, a topic we have addressed in past member conversations. We remain interested in this idea and are exploring the potential to gather a group of sponsors to pilot a fund model.

Confronting the infinite horizon of mission - how to draw the line?

It’s not always easy to wake up every morning and confront the infinite potential of your nonprofit mission and vision. Most days (we hope!) it’s inspiring work, but it can also be overwhelming. Even in the case of missions focused on more quantifiable needs, such as the number of kids in a given school district in need of a healthy lunch, there is always more than can be accomplished. For missions with less quantifiable bounds, such as supporting the creative vision of artists, advocating for social justice, or nurturing a faith community, the potential for growth is infinite.

Yet making the hard decisions to define our scope of impact at any given time is essential to being able to describe and demonstrate impact. Otherwise, we live in a state of constant over-promise and under-delivery. Essential to this task is thinking about scale and impact as having both qualitative and quantitative dimensions. It’s as much about how much as it is about how well or comprehensively we deliver our work. In a world obsessed with numeric and financial metrics for scale, arguing that we want to serve fewer students, but more immersively can sometimes be hard. But growth and scale can be determined by the depth of services offered, as much as by the number of people served.

Finally, setting boundaries, being focused, and cultivating the fine art of saying “no” are essential to maintaining our morale, life-work balance, and overall mental and physical health. Five hundred years ago, scholars and philosophers in the West began writing about melancholia (the origin of our word melancholy), a mild depression or sense of unease brought about by contemplating the vastness of the universe and the divine. In like manner it’s easy to succumb to the weight of the water we carry in the nonprofit sector. The enormity of the problems we seek to address can often overwhelm. But rest assured that in applying intentional consideration to the questions of scale and defining our limits at any given moment, we can chart a path to organizational health and impact, one step at a time, one scope at a time.